Things To DoEncounter History & Heritage

Stronsay Heritage

New for Summer 2025—Stronsay Heritage Trail, including the Boatie Hoose and Tidal Toilets

Made possible by funding from the North Isles Landscape Partnership, the new 1.25 mile (2 km) Stronsay Heritage Trail is intended to help visitors and locals alike appreciate the centuries-long heritage of Stronsay’s Whitehall Village and along the shoreline stretching to the north-east and north-west. The trail includes eight interpretation boards and twenty-one plaques which highlight both the important and the everyday of Stronsay’s main industries and cultural life, including archaeology, the Lifeboat, Herring Fishing Curing Stations, the varied roles of Stronsay’s piers, the Fish Mart, and the Bay of Franks. One board overlooking Papa Stronsay offers an introduction to Stronsay’s sister island.

The newly renovated Boatie Hoose invites visitors to step inside, where several interpretation boards describe the fascinating journey of a lifeboat (now the roof for the structure) – from the torpedoed passenger liner Athenia in 1939 to ‘tangy boat’ to Boatie Hoose. A few steps away is the restored building housing the tidal toilets, which is also well worth a look.

For those who want to know more, web pages accessed through QR codes on the interpretation boards or through the Stronsay Heritage Society’s website accompany the trail. A brochure describing the trail can be picked up at most businesses in Whitehall Village. And, of course, a visit to the Stronsay Heritage Centre brings even more life and depth to the sites mentioned on the trail through photographs, artefacts, books and other documents.

Stronsay Heritage Centre

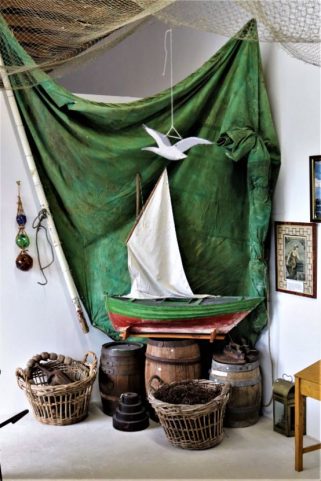

The Stronsay Heritage Centre is located in one of the units at Wood’s Yard at the west end of Whitehall Village (within walking distance from the ferry pier). Open every day, the building displays artefacts important to Stronsay’s natural and cultural heritage. Recently added display cabinets highlight the accordion on which the “Stronsay Waltz” was composed, and one of the Harbour Log Books, which offers a fascinating overview of the busy-ness of the herring fishing days. Those with an interest in family history will find many helpful documents, including census, baptismal, and cemetery records, and many albums of carefully labelled photographs to pore over.

The Heritage Centre is a great place to sit on a rainy day (not that there are many of those!) with a hot drink (tea/coffee-making facilities are available). This location is temporary, and interpretation for the artefacts is still being developed, as are plans for the new stand-alone Heritage Centre, which is hoped will open to the public in 2026. Entry is free, though donations are always welcome.

For more information about either the Heritage Trail or the Heritage Centre, please contact heritagesocietystronsay@gmail.com.

One of the truly amazing aspects of Stronsay is the way in which past and present often rather casually overlap and interact.

Stronsay born and bred, Molly Shearer has reflected her own farming/fishing/weaving heritage, as well as that of the island, in this beautiful artwork which hangs in the waiting room at the pier. Stronsay artist Nathan MacTaggart designed and crafted the herring fish hanger.

People have been living in Stronsay longer than the imagination can truly take in. Layer upon layer, history unfolds, and the heritage of this powerful legacy continues to impact the present. Hunters and gatherers, farmers and fishermen, Picts and Vikings, lairds and crofters, coopers and gutter girls, priests and pastors, shopkeepers and housekeepers, farm servants, weavers, bakers and knitters, not to mention countless generations of school children — the heritage of many eras are all around you if you know where to look.

You can take a walk out to Lamb Head and stand next to the remains of a broch that was built by Stronsay inhabitants nearly two thousand years ago and, looking around, see numerous wind turbines generating power for modern, eco-friendly homes. You can inspect the current fishing fleet tied up at the West Pier and imagine being able to walk from one pier to another across the decks of the boats tied up during the peak of the herring fishing era in the 1920s. Every year while ploughing, present-day farmers uncover items their ancestors left behind 100, 1,000 — even 8,000 years ago!

The many layers of the past have shaped the history and heritage inherited by the current generations of islanders, who, in turn, will impact those yet to join their numbers.

Archaeology

Stronsay is very modest about its archaeological riches. Though Canmore lists over 417 sites of historical interest on the island, to date there has been little development of any of them, especially the most ancient ones. They are not completely hidden, though. Triangular hillocks marking the location of cairns jut up from higher points on the shoreline or in the middle of the islets or holms surrounding Stronsay. Rounded hills rise slightly out of flat plains and depressions mark something not far below the surface. Traces of the treb dykes used to enclose fields in the Bronze Age are still visible on Burgh Head. Piles of stones carefully laid on top of each other indicate manmade structures of one kind or another constructed at some point along the timeline of Stronsay’s human habitation.

Stronsay is very modest about its archaeological riches. Though Canmore lists over 417 sites of historical interest on the island, to date there has been little development of any of them, especially the most ancient ones. They are not completely hidden, though. Triangular hillocks marking the location of cairns jut up from higher points on the shoreline or in the middle of the islets or holms surrounding Stronsay. Rounded hills rise slightly out of flat plains and depressions mark something not far below the surface. Traces of the treb dykes used to enclose fields in the Bronze Age are still visible on Burgh Head. Piles of stones carefully laid on top of each other indicate manmade structures of one kind or another constructed at some point along the timeline of Stronsay’s human habitation.

Mesolithic Settlement Site

Mesolithic Settlement Site

Though the reality of what has been discovered on the island is still sinking in and the wider repercussions of the find are just beginning to be acknowledged and celebrated not only in Orkney but further abroad, something very exciting has been uncovered in Stronsay. In 2008, the remains of post holes and rare tanged flint points in a field belonging to Links House indicated that this excavation was revealing something very unusual — even for Orkney. Those who have carefully studied the finds have since determined that this site comprises the oldest manifestation of human habitation in the whole of the North of Scotland — a settlement dating from the Mesolithic period (c. 8,000 years old!). Though the site itself has been covered over again while the archaeologists go in search of more funding, the island is hoping to obtain some of the finds to add to displays in the Heritage Centre and, in partnership with Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology at Orkney College, University of the Highlands and Islands, to make this discovery accessible to the wider world. To read more about the dig in the Friends of the Orkney Archaeological Trust Report (Spring 2008, pp. 9-12), click here.

To view a brochure showing a map of known archaeological sites in Stronsay and describing Stronsay’s archaeology in more detail, click here.

Early Chapels and Churches

Archaeological remains in Stronsay and Papa Stronsay point to the arrival of Irish hermits and Pictish Christian clerics in the late 600s. The remains of St Nicholas chapel on Papa Stronsay, excavated between 1998 and 2000, date from the 11th century. Below this structure are the remains of a Pictish Christian Chapel, perhaps from the 700s. And beneath that earlier chapel are signs of a Late Iron Age settlement! Traces of two enclosures of what were probably medieval hermitage sites can be seen atop two of the sea stacks beyond the Vat of Kirbister. In the medieval period, Stronsay was divided into three parishes, St Peter, St Mary and St Nicholas. Though the churches themselves are no longer standing, each site still houses a graveyard that can be visited. To read more about this period of Stronsay’s history and details about the archaeological dig in Papa Stronsay, click here.

Archaeological remains in Stronsay and Papa Stronsay point to the arrival of Irish hermits and Pictish Christian clerics in the late 600s. The remains of St Nicholas chapel on Papa Stronsay, excavated between 1998 and 2000, date from the 11th century. Below this structure are the remains of a Pictish Christian Chapel, perhaps from the 700s. And beneath that earlier chapel are signs of a Late Iron Age settlement! Traces of two enclosures of what were probably medieval hermitage sites can be seen atop two of the sea stacks beyond the Vat of Kirbister. In the medieval period, Stronsay was divided into three parishes, St Peter, St Mary and St Nicholas. Though the churches themselves are no longer standing, each site still houses a graveyard that can be visited. To read more about this period of Stronsay’s history and details about the archaeological dig in Papa Stronsay, click here.

Viking History and Stronsay in the Orkneyinga Saga

Norwegian settlers arrived in Orkney in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, and although the islands were used as bases for Viking raids elsewhere, most of the settlers were farmers, raising cattle and sheep. The abundance of Norse names of farms and fields are the heritage of the history of Norse settlers in Stronsay, and several sites have been noted as Viking settlements. Though not always for the noblest of reasons, Stronsay even gets several mentions in the Orkneyinga Saga (dating about 1225, but based on an even older oral history of Viking notables). To read the text for yourself, click here and look especially for chapters XVIII and XXXII.

The Name ‘Whitehall’

Stronsay-born Patrick Fea (1640-1709) is credited with introducing the name by which Stronsay’s village is now known. Whether by fair means or foul (the debate is still open on this), over the course of his seafaring adventures, Fea managed to amass a great deal of capital — enough to build a large house near the head of the present ferry pier. He called his house ‘Whitehall’, and gradually, the fishing village, which had previously been known as Strenzie, began to take on the name of the house.

Stronsay-born Patrick Fea (1640-1709) is credited with introducing the name by which Stronsay’s village is now known. Whether by fair means or foul (the debate is still open on this), over the course of his seafaring adventures, Fea managed to amass a great deal of capital — enough to build a large house near the head of the present ferry pier. He called his house ‘Whitehall’, and gradually, the fishing village, which had previously been known as Strenzie, began to take on the name of the house.

The Name ‘Rothiesholm’

Hugh Marwick captures the essence of this term when, in his Antiquarian Notes on Stronsay, he refers to it as ‘a very difficult name’. The spelling of the name has certainly undergone various transformations through the centuries, but Marwick says the clue to its origin is precisely the fact that it is no longer pronounced as spelled. The first part of the name likely stems from the Old Norse word for ‘red’ (rauðr) — presumably for the colour of the cliffs on Rothiesholm Head — and ‘head’ (hofuð) or ‘harbour’ (homn). The most important thing for you to know, however, is that the locals now pronounce it ‘Rousam’ (‘Rou-‘ rhymes with ‘how, now, brown cow’ — unless you’re Orcadian, that is…).

The History and Heritage of the Kelp Industry in Stronsay

Although Stronsay’s kelp was known far and wide for its healing powers (especially if taken with the waters flowing from the Well of Kildinguie) and attracted many visitors to the island during the medieval period, it was during the early 1700s that kelp was discovered to be a money-making resource for a different reason.

Stronsay man James Fea of Whitehall introduced Kelp making to Orkney in the early 1720s, and it rapidly replaced grain as the county’s biggest export. Whereas seaweed had previously served primarily as fertiliser, the islanders were encouraged to collect and burn it and sell it for a small sum to the lairds, who would then make a huge profit by sending it on to be used for soap, dye and glass production in Scotland and North East England. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), when kelp from the Mediterranean region was not available, Orkney kelp was in high demand, and thousands of Orcadians were involved in its production–though many were compelled by their landlords to do so.

was not available, Orkney kelp was in high demand, and thousands of Orcadians were involved in its production–though many were compelled by their landlords to do so.

A handful grew very rich and, true enough, many were kept from starving, but the industry was far from popular for a number of reasons (not least the horrible smell of the thick smoke). Things got so bad at one point that there were even riots in Stronsay! To find out more about what happened, take a look at an article written by Stronsay native Jim Cooper.

When the wars ended, the bottom dropped out of the market and caused many an economic hardship. The industry experienced a revival in the mid-1800s when iodine, which can be extracted from seaweed, began to be used as an antiseptic. Kelp as a source of iodine was again in demand during the First World War, but the industry gradually declined again until it was almost extinct in the mid-1930s. With the growth of Alginate Industries (formerly Cefoil Ltd.), the importance of kelp making in Stronsay flourished again for a brief time in the 1960s. And tangles were gathered, dried and shipped from Stronsay in the 1970s and 80s. To read an eyewitness account of the kelp industry in the mid-20th century, written by Stronsay-native Nana Peace, click here.

Present-day visitors can still find signs of the kelp industry by walking east out of the village and along the shore of Grice Ness, where long stone beds (beeks) can be found. Those who venture along Odness point may also find remnants of the kelp pits.

Present-day visitors can still find signs of the kelp industry by walking east out of the village and along the shore of Grice Ness, where long stone beds (beeks) can be found. Those who venture along Odness point may also find remnants of the kelp pits.

Much more information about the history and heritage of the kelp industry in Stronsay can be found in the Heritage Centre.

The Heritage of Herring Fishing in Stronsay

(The text for this section is adapted from the photo display boards currently found in the Fish Mart Cafe.)

The history of herring fishing in Stronsay stretches back to the late 16th century when Dutch fishermen were operating around Stronsay, with shore bases on the island. David Drever, the farmer of Huip, started the herring fisheries in Stronsay in 1814, and in 1816, local landowner Samuel Laing of Papdale (now part of Kirkwall) invested in a herring curing station. He also commissioned the building of a pier, as well as accommodation for the fishermen and gutters.

The history of herring fishing in Stronsay stretches back to the late 16th century when Dutch fishermen were operating around Stronsay, with shore bases on the island. David Drever, the farmer of Huip, started the herring fisheries in Stronsay in 1814, and in 1816, local landowner Samuel Laing of Papdale (now part of Kirkwall) invested in a herring curing station. He also commissioned the building of a pier, as well as accommodation for the fishermen and gutters.

In the first half of the 19th century, men who worked small crofts supplemented their income by fishing, going out overnight in small Orkney yoles to catch the herring in nets.

New larger fishing boats arrived from the north-east of Scotland in the late 19th century. Scaffies, Fifies and Zulus replaced the small Orkney boats and increased the quantity of herring landed in Stronsay, which became the main herring fishing port in Orkney. The harbour was improved; new curing stations opened and Papa Stronsay was also developed as curing stations with private piers being built. In the early 20th century, Stronsay received a boost when new markets were established with Germany and Russia. The sailing ships were, in turn, replaced by steam drifters that could catch more fish and sail in calm weather. Coal hulks lay offshore and supplied the drifters with the fuel that they needed. By the outbreak of World War I, steam had all but taken over from sail. Fishing stopped during the war, but with government aid, it began again in 1919.

The herring industry brought much needed money into Orkney and was a great source of employment  for many. Every year, shoals of herring migrated around the coast of Britain from west to east. Their arrival heralded huge activity, as fishing ports were turned over to the landing and processing of the ‘silver darlings’. The herring arrived at Shetland in June, then moved south to Orkney by mid-July and throughout August. They continued their southward route, bringing work to the east-coast fishing towns of Scotland and England. The fishermen followed the herring shoals and an army of ‘gutters’ arrived to gut the fish and remove the gills in one quick movement. These girls mostly came from the Western Isles and Moray Firth, but local girls were also employed. They worked in groups of two or three; two gutting and one packing.

for many. Every year, shoals of herring migrated around the coast of Britain from west to east. Their arrival heralded huge activity, as fishing ports were turned over to the landing and processing of the ‘silver darlings’. The herring arrived at Shetland in June, then moved south to Orkney by mid-July and throughout August. They continued their southward route, bringing work to the east-coast fishing towns of Scotland and England. The fishermen followed the herring shoals and an army of ‘gutters’ arrived to gut the fish and remove the gills in one quick movement. These girls mostly came from the Western Isles and Moray Firth, but local girls were also employed. They worked in groups of two or three; two gutting and one packing.

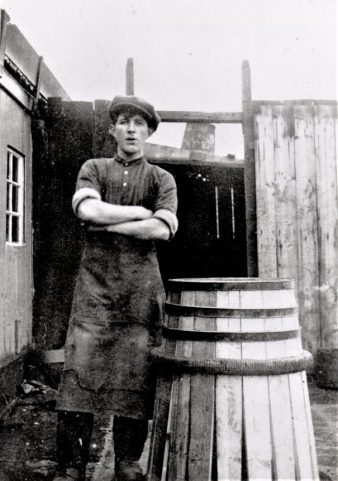

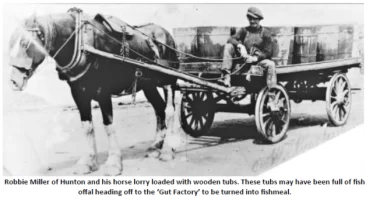

Many locals worked in various ways to support the land-based side of the business. The curing yards brought in tons of salt, while coopers prepared and checked the barrels that the herring would be packed in. The fish were sold at auction in the Fish Mart. A sample of the fish was taken in a basket to the auction room where the curers bid for it. The fish were then transported to the curing station by boat to private piers or by horse and cart to the curer’s yard. The fish were rubbed with salt to revive the quality of the herring and to make it easier to handle. They were emptied into a large trough where they were gutted and sorted depending on quality. Finally, they were packed in salt-covered layers ready to be taken away by ship.

From the 18th century right up to the outbreak of World War II, the seasonal influx of workers would see the population swell to as many as 5,000, and the boats queuing to unload their cargoes were so numerous that it was possible to walk across their decks to the isle of Papa Stronsay without ever getting your feet wet!

Due to the Second World War and depleting fish stocks, the herring industry in Stronsay gradually came  to an end. But fishing — now primarily for brown, green and velvet crabs and lobsters — is still an important part of Stronsay’s economy. After a day’s fishing around Stronsay, the local boats tie up along the West Pier, and just before they are sent into Kirkwall with the haulier, the boxes of the week’s catch stretch out in the harbour — a testament to the skills that have been handed down through the generations. However, if you ask how things are going, you’re likely to be told that it’s been ‘another poor week’.

to an end. But fishing — now primarily for brown, green and velvet crabs and lobsters — is still an important part of Stronsay’s economy. After a day’s fishing around Stronsay, the local boats tie up along the West Pier, and just before they are sent into Kirkwall with the haulier, the boxes of the week’s catch stretch out in the harbour — a testament to the skills that have been handed down through the generations. However, if you ask how things are going, you’re likely to be told that it’s been ‘another poor week’.

Signs of the heritage of the herring industry can still be found in Stronsay. The Fish Mart is now a cafe and hostel, and some artifacts, maps and photographs from the herring fishing days are displayed on the walls of the cafe. The Heritage Centre has much more information, binders of photographs and many objects that can be seen.

Signs of the heritage of the herring industry can still be found in Stronsay. The Fish Mart is now a cafe and hostel, and some artifacts, maps and photographs from the herring fishing days are displayed on the walls of the cafe. The Heritage Centre has much more information, binders of photographs and many objects that can be seen.

If you’d like to read an eyewitness account of life during the herring fishing days, please click here.

A Heritage of Learning, Crafts and Skills

Here is a bit of information that could prove helpful at your next quiz night: Where was the first library in Scotland established? The answer, of course, is — Stronsay! At Holland Farm, to be exact. In 1670, William Baikie acquired the farm of Holland from his father, and being a scholar and bibliophile as well as a farmer, Baikie amassed a good collection of books, which he bequeathed to the people of Orkney through his friend James Wallace, the minister of the Kirkwall Cathedral, who used the collection to establish the public lending library in Scotland. Baikie’s collection was added to through the centuries, but his books, with their neat anotations in the margins, still form the heart of the present Orkney Library and Archive. Baikie was known to be both a compassionate landlord and an encourager of Stronsay children who wanted to learn. (To read more about Scotland’s first library, click here.)

Stronsay’s children have been well educated in a number of schools, located in the various parishes of the island: North School, Central School (the present site of Stronsay Junior High School), South School and the Rothiesholm School. The Heritage Centre has a folder full of school photos stretching back through the decades. Perhaps you can find yourself, an old friend, or an ancestor sporting a wide toothless grin or scowling down at too-tight shoes in one of the photos.

Stronsay’s children have been well educated in a number of schools, located in the various parishes of the island: North School, Central School (the present site of Stronsay Junior High School), South School and the Rothiesholm School. The Heritage Centre has a folder full of school photos stretching back through the decades. Perhaps you can find yourself, an old friend, or an ancestor sporting a wide toothless grin or scowling down at too-tight shoes in one of the photos.

Stronsay has also long been known for the skills of its craftsmen and women. Weaving, straw work and knitting have been important industries. Examples of these crafts can be seen in the Heritage Centre.

Agricultural History and Heritage

Stronsay is flat and fertile, which makes an ideal farming community, and there are signs that even the earliest of inhabitants drew on the abundant natural resources all around them. Remnants of ancient (Pictish) agricultural practices can still be seen in what are known as Treb Dykes on Burgh Head in Stronsay. These earthen mounds (dykes) may have represented boundary walls or enclosures near settlements.

Farms during the Norse period tended to be large, owned by a few wealthy men, until all land was passed to the King of Scots in 1470. In Stronsay, there was only one tiny parcel of privately owned land, while most land was owned either by the earl or bishopric of Orkney. Large farms supported up to twenty households. The tenant farmers worked according to the runrig system, where long strips of land were allotted with the aim that everyone got at least a bit of good ground and bit of the foreshore. In between these cultivated strips was uncultivated land or common land for grazing. (To read more in depth about land use in early Orkney, click here to open a PDF from NatureScot.)

In the early 19th century, land owners were swept up by the lure of the more lucrative kelp industry and agriculture gained less of their attention. However, when the market collapsed at the end of the Napoleonic wars, minds were focused again on land use and many improvements began to be introduced; for example, the runrig field patterns were replaced with square fields. Especially after 1845, the raising of beef cattle and cultivating of turnips came to the fore. Steamships opened up new markets on mainland Britain, and goods could be moved more efficiently and less expensively. Enclosures were built, new ploughs were trialled, new types of seed and livestock were introduced and mills were constructed.

By the end of the 19th century, more land had been made arable, but the raising of livestock predominated. After the First World War, many small crofts were sold, and farms began amalgamating under  single ownership. Sheep numbers doubled and cattle numbers increased by a third. High quality breeds led to Orkney’s reputation for quality beef, sheep and eggs. The introduction of the tractor in the 1920s began to replace the horseman and his team, who could plough about an acre a day.

single ownership. Sheep numbers doubled and cattle numbers increased by a third. High quality breeds led to Orkney’s reputation for quality beef, sheep and eggs. The introduction of the tractor in the 1920s began to replace the horseman and his team, who could plough about an acre a day.

Stronsay native Ian Cooper has gathered much in-depth and interesting historical information as well as anecdotes from Stronsay farmers of a previous generation. To read a couple of his articles — one discussing agricultural improvements in the 19th century — click here for part 1 and here for part 2– and one dedicated to the introduction of the tractor-driven binder at Holland Farm in Stronsay in the late 1940s or early 1950s, click here.

Since 1940, there has been a shift away from arable to pasture, with hay being replaced by silage. In the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, there was an increase in the number of cattle and sheep on Stronsay, while the numbers of horses, pigs and poultry declined. Primary crops were bere (an old type of six-rowed barley, later superseded by spring barley), oats, potatoes and turnips.

Today, there are about twenty-five farms in Stronsay, mostly raising beef cattle and sheep, and a variety of breeds can be seen grazing contentedly in the lush green fields (though the coos go in about October and re-emerge end of April/early May). Most farms grow the majority of their winter feed, with good quality silage and some hay. Barley is the main cereal crop. Most animals are sold through Orkney Auction Mart, though some are sent to Aberdeen and other outlets.

Today, there are about twenty-five farms in Stronsay, mostly raising beef cattle and sheep, and a variety of breeds can be seen grazing contentedly in the lush green fields (though the coos go in about October and re-emerge end of April/early May). Most farms grow the majority of their winter feed, with good quality silage and some hay. Barley is the main cereal crop. Most animals are sold through Orkney Auction Mart, though some are sent to Aberdeen and other outlets.